Donald Trump has a new website. A lot of the coverage I have read is about how it is essentially a blog filled with tweet-sized rants (example coverage).

I think the most notable aspect of the website is how transparently and aggressively it is optimised to be a money-making machine.

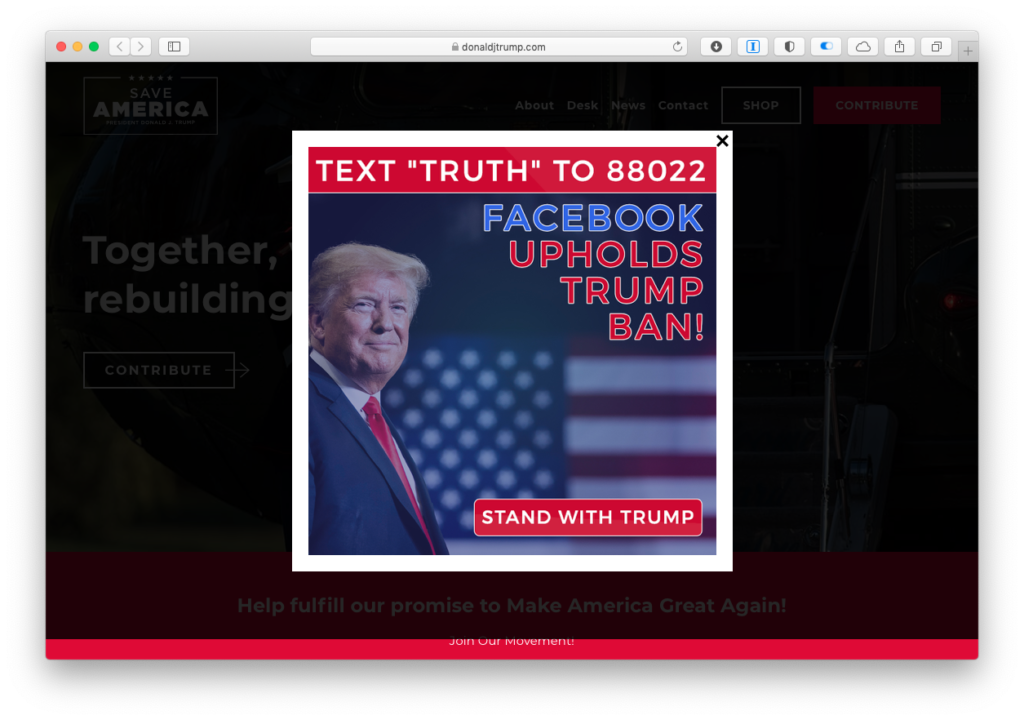

Here is my experience (I am outside the US). This popup greets you when you visit the site.

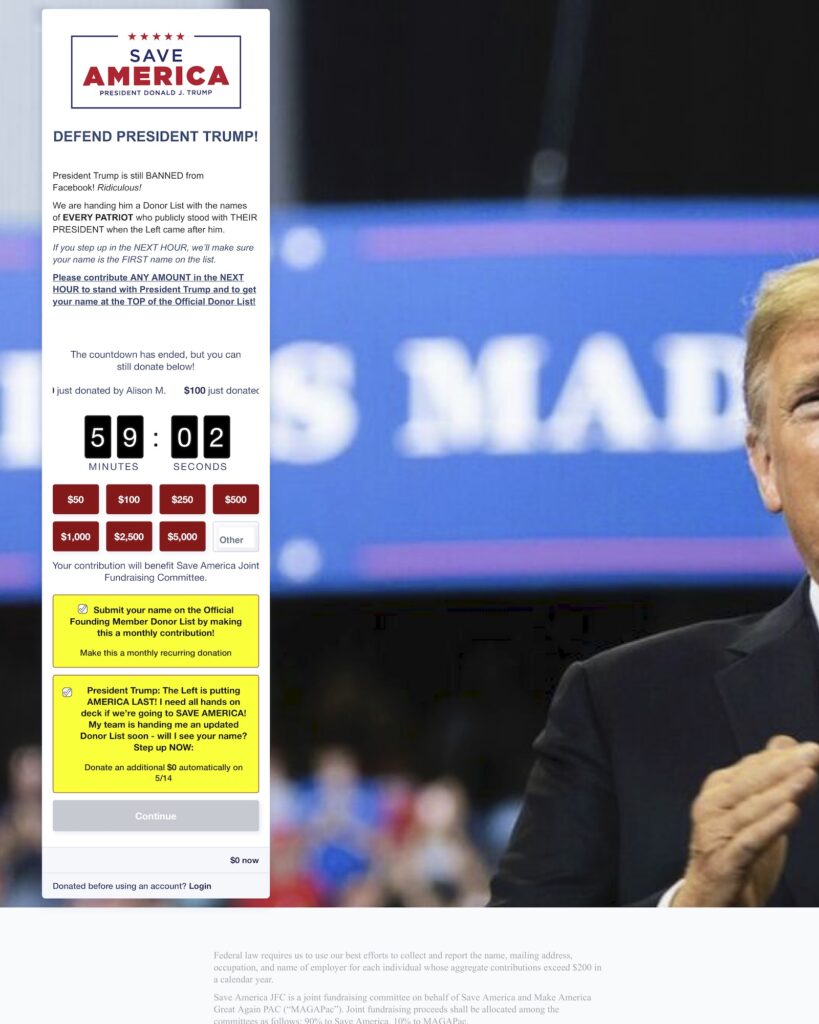

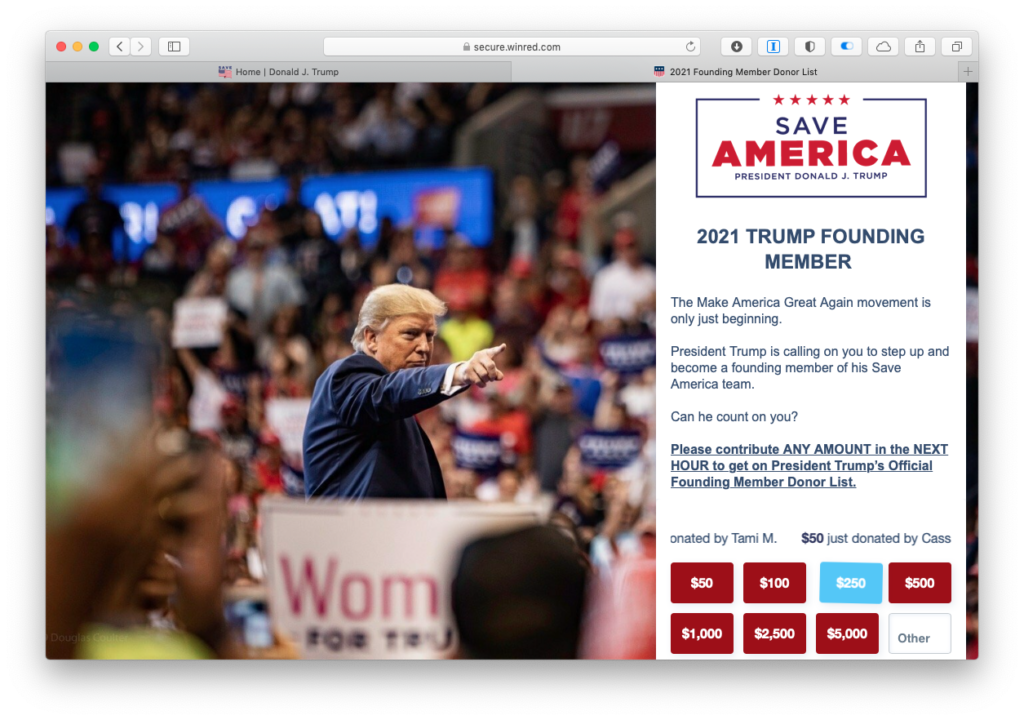

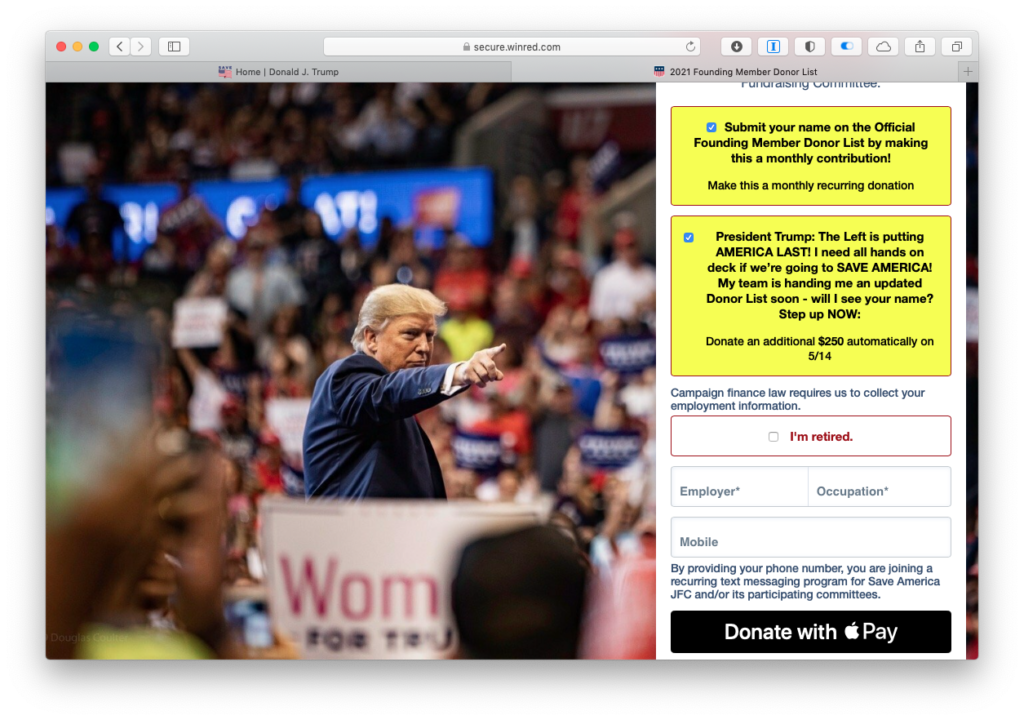

Tapping on it leads you to this.

This is the same text and design that led people to unwittingly sign up for repeated donations from their bank accounts – in some cases until their account was empty [1].

The text is endearingly deceptive, panders to ego and assumes lack of attention. For example, “If you step up in the NEXT HOUR, we’ll make sure your name is the FIRST name on the list” with a large timer counting down from one hour. But also in the middle of it all, “The countdown has ended, but you can still donate below”

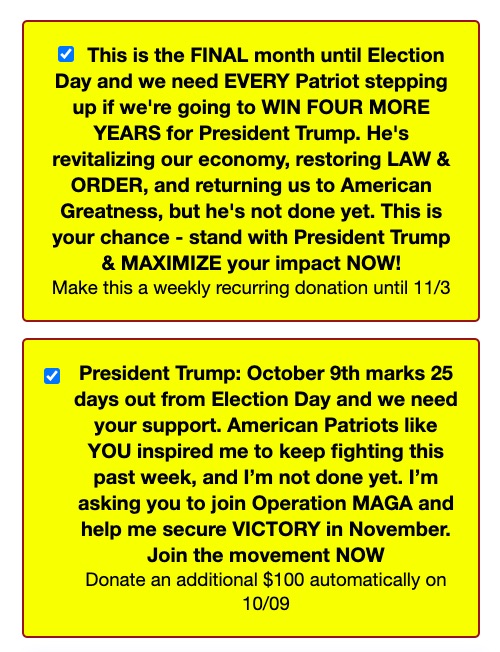

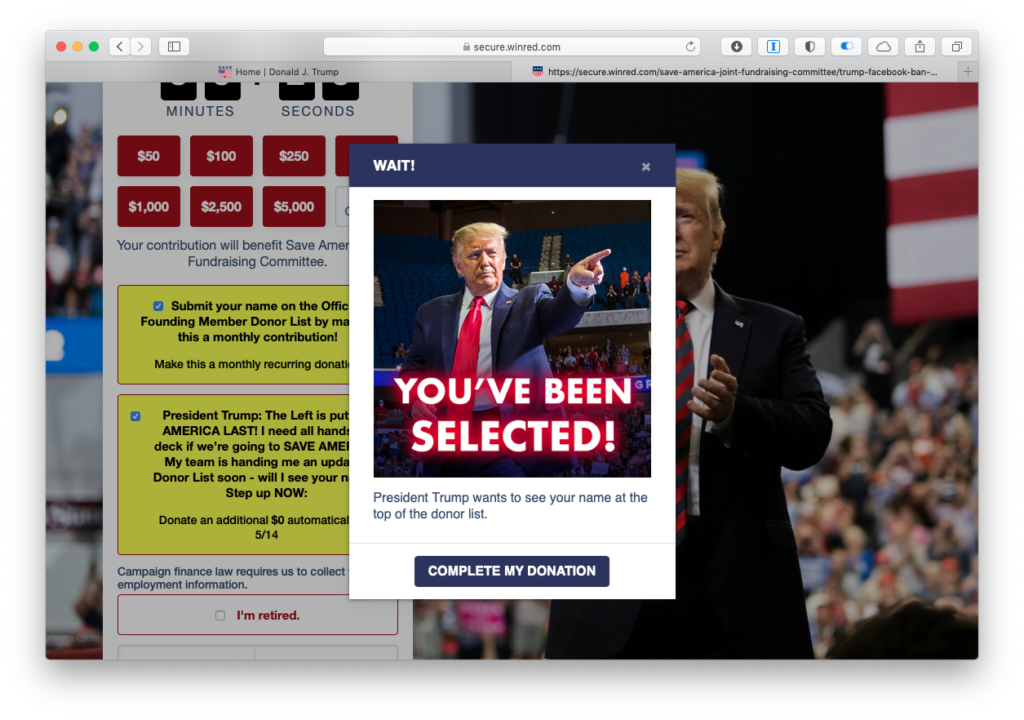

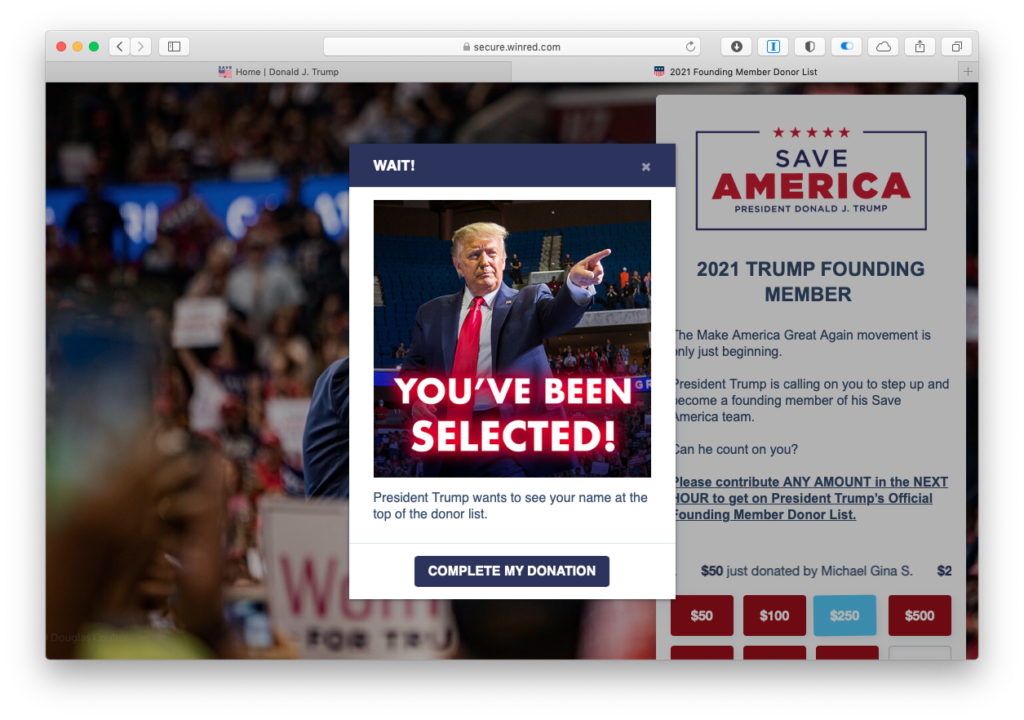

If you linger too long on the page, you get this other popup informing you that the ex-president wants to see you on the ‘top of the donor list’, whatever that means. Tapping ‘complete my donation’ simply dismisses the popup, but presumably you are now more likely to finish the transaction.

All of this is before you’ve even seen the home page of the site itself.

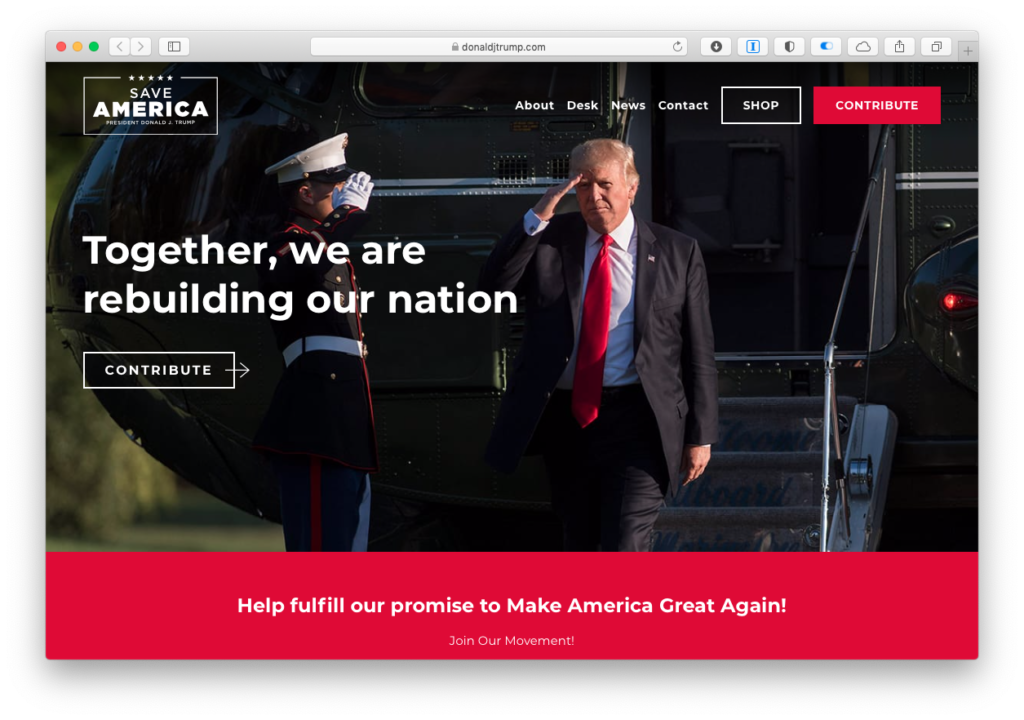

Anyway. You navigate back to the popup and dismiss it. Here is the actual home page:

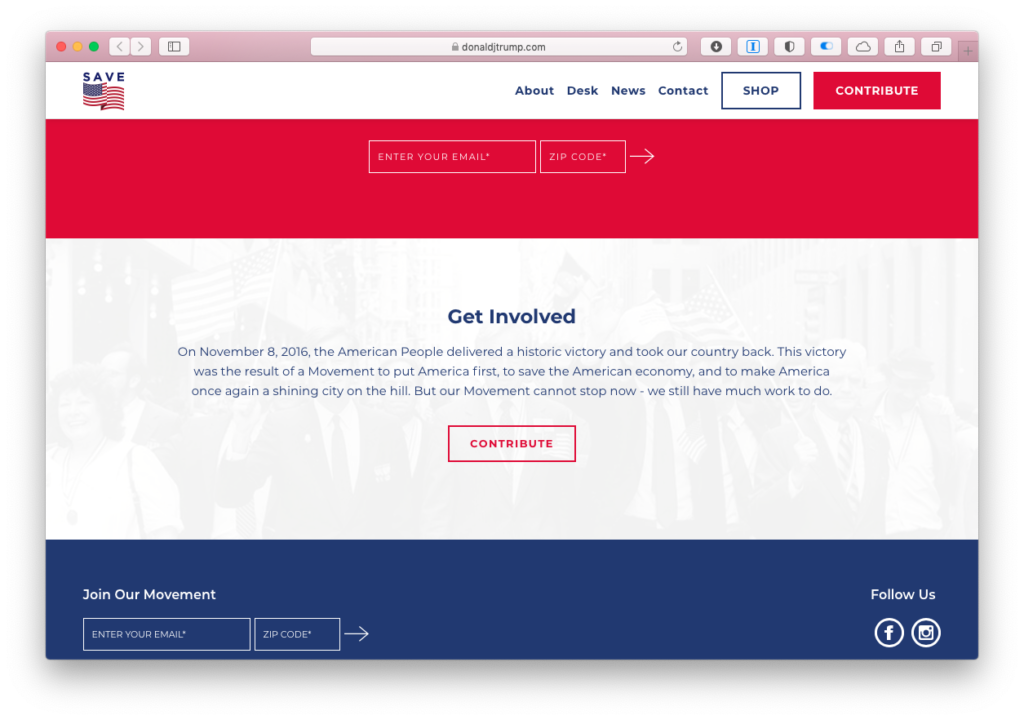

There are three buttons on this screenful, and none of them have anything to do with what Trump has to say. They all have to do with money. Scrolling down, you get yet another contribute button.

The focus of the coverage, Trump’s new blog, is behind that tiny ‘Desk’ link at the top. It’s clear what Trump wants his supporters to click on.

So. Since ‘contribute’ is the main call-to-action, let’s tap on it. You’re taken to a page looks very much like the one you were taken to right at the beginning, complete with hard-to-notice default opt-ins.

Donating on the earlier page would put you on the ‘official donor list’. Donating here would put you on the ‘official founding member donor list’.

If you linger here, the same popup as earlier nudges you.

I couldn’t contribute because I am not “a U.S. citizen or lawfully admitted permanent resident”, so I haven’t experienced what happens after.

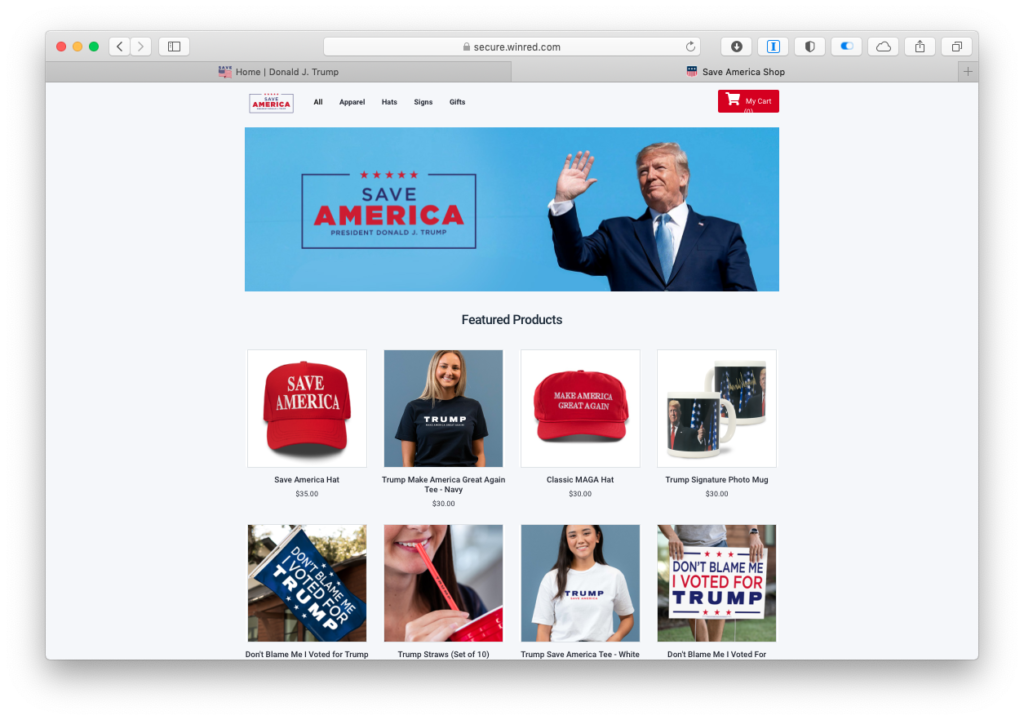

But if you navigate back and tap on the other major button, ‘Shop’, you’re taken to this store:

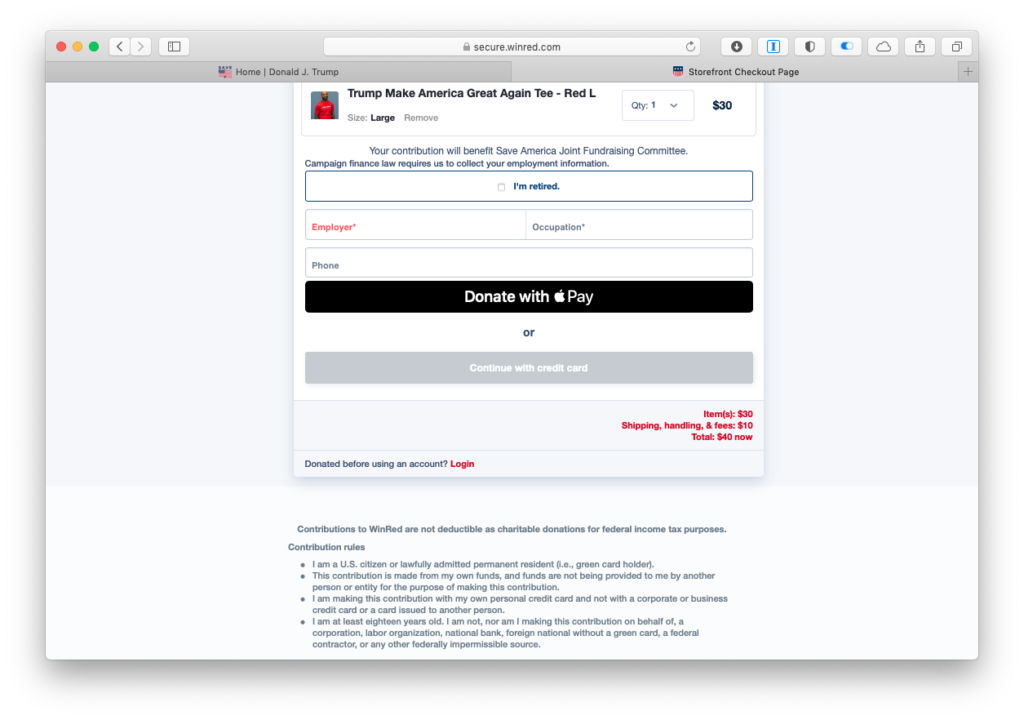

This is the checkout page:

When you check out an item, you aren’t buying it. You’re still donating. Even when you’re in the ‘Save American Shop’. I’m not sure if this is standard practice across USA political organisations.

I’m also not sure if the ten dollars for ‘shipping, handling and fees’ is normal. I’ve never bought items on a USA website. Seems somewhat high.

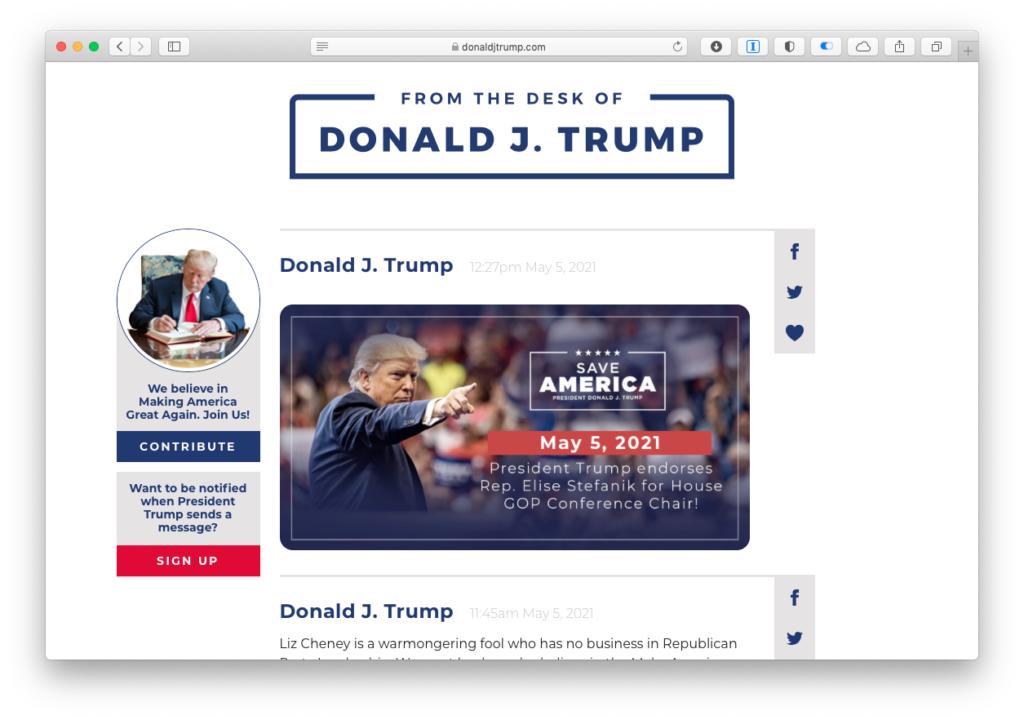

Finally, when you do tap on Desk, that tiny link at the top that is the center of all the coverage about Trump’s new online presence, this:

The first button, the first actionable click on the screen is the ‘Contribute’ button. Right alongside the post. Bolder than the actual text of the posts themselves.

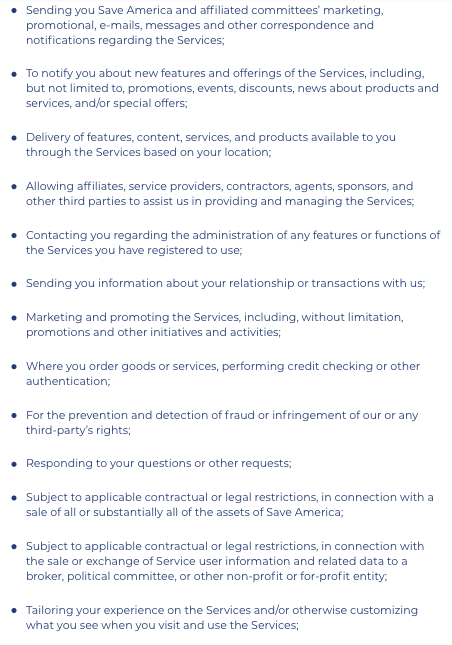

One last thing. The privacy policy makes clear what the organisation can do with your data:

We reserve the right to use, share, exchange and/or disclose to Save America affiliated committee and third parties any of your information for any lawful purpose, including, but not limited to, as described in Section 3.

And what’s in section 3? All this and more:

This gives the organisation the ability to monetise your data, over and above the contributions you make to it.

So.

The site makes no pretence about who it is for. It doesn’t seek to convert; it’s for the faithful. Back in January, we had discussed this when several of Trump’s social media accounts were suspended:

Anyone who engages with Trump and his community on this [then-not-yet-live] website and forums is someone who has joined for that specific reason. No one other than news reporters covering Trump and his network will join.

– Where will the Trump community congregate after the Twitter and Facebook ban?

Because it’s for the faithful, the site doesn’t need to create talking points; the 24×7 news cycle of outrage creates them already. He knows that his opinions will be picked up by news websites and channels and social media personalities even if they are buried deep on his site. Why, those people have probably set up alerts for new posts.

The true utility of the people who actually visit those site, the ordinary right-wing USA citizen, is their money. That is what Trump’s website is for. And it has done a truly outstanding job.

[1] The donations infrastructure is by Winred, which describes itself as “the official secure payments technology designed to help GOP (ie Republican) candidates and committees win across the US.” Winred appears to have a monopoly on online Republican fund-raising.