Recently, the founder of an Indian stockbroking company wondered whether it was right that the Indian stock indexes were doing well in the midst of abject suffering.

A few days later, there was news about the USA government possibly intervening to override vaccine patent protections to make them more widely available. The stocks of companies involved in vaccine manufacturing fell, prompting this:

I remember in late 2019, before the pandemic, there was a credit squeeze problem in India. The last eighteen months have nearly erased that memory, but loans had gone bad then, a few high-profile companies defaulted on their debts, and it became hard for companies to get loans to expand their business. Even so, the Indian stock market then reached record highs. I remember similar judgements on whether it was moral for the indexes to do so well.

When people refer to the ‘stock market’ they’re usually referring to the flagship index, which is a collection of a few dozen stocks. The ‘market’ rising or falling on any given day is an outcome of how those stocks do. And whether a stock rises or falls is an outcome of what people think and feel about the prospects of that company in the future. For some, the future means the next day. For others, it means the next decade.

All this is to say that a stock, and the ‘stock market’ isn’t an entity of its own. It’s made up of investors like you and me and larger trading institutions, domestic and foreign.

Ascribing morality to the stock market is pointless.

Let’s think this through further. Here are the companies that together make up the thirty stocks in the ‘Sensex’ and the fifty stocks in the ‘Nifty’:

When the Zerodha founder, an obviously immensely successful businessman and investor, wonders why the market hasn’t fallen, is he saying that he in fact expects these companies to do worse in the coming months, and that people who hold these stocks don’t understand this?

Or is he making the moral case, that markets ‘should’ drop in solidarity with the mood of the country? Because then he’s saying that people should sell their stocks out of such solidarity, regardless of what they feel about the prospects of the company.

And let us not forget that when someone sells, someone else needs to buy. When people sell their Tata Steel shares en masse because the stock, and the market, must suffer, they’re selling those shares to other people. If Tata Steel is fundamentally a good company, it will do well, there’ll be demand for its shares during and after the pandemic, and its price will rise again. Who benefits? The other people who bought the shares. Who misses out? People who sold them.

So who should suffer and whose expense, and for what? Who decides this?

Or take the other person whose tweet I pasted. They seem to imply that it is immoral for people who hold pharma company stocks to sell them when they hear news of patent protections being suspended. In other words, he thinks the following: Maggie, who in 2020 read about Moderna’s research into a vaccine and bought the stock anticipating that the company would make money off the vaccine, and who now hears that Moderna stands to make less money than it seemed last year, should nevertheless hold on to her stock because it is the moral thing to do.

According to this person, what should Maggie do when Moderna does inveitably announce that it’s made less money in 2021 than it projected in 2020? Should she only sell the stock at that time, despite knowing about lower earnings months earlier? Or does morality dictate that she hold on to it?

Who is Maggie being moral to? Other investors? But they are beholden to the same morality as she is. Who enforces this morality and, more importantly, who benefits from it?

Implicit in all this is the notion of ‘investors’ being greedy, unprincipled people. That they are not you and me; they are out to fleece you and me. And so no wonder ‘they’ do well even as the ‘rest of us’ are going through a hard time.

The reality is simply that people who hold stocks of fundamentally good companies benefit from these companies doing well – making good products, selling them in India and overseas, growing their sales year after year while also being prudent with their expenses. Why do these people benefit? Because the share price of such companies rises as they do well [1].

So instead of punishing both the companies and their stock-holders to suffer along with the rest of the country for abstract reasons of ‘right-ness’ and morality and solidarity, why not have as many Indians as possible benefit from India’s best companies? Ergo, why not make as many people stock-holders as possible?

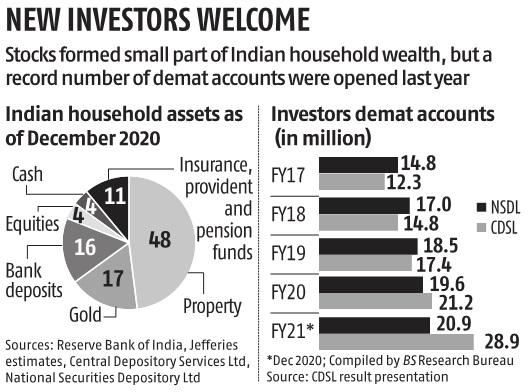

In India, there are less than fifty million ‘demat’ accounts, or accounts via which stocks are bought and sold [2]. Since many investors have more than one demat account, let’s assume there are forty million actual people with such accounts. Let’s assume that all of them hold a meaningful amount of stocks in them (a wildly optimistic assumption). That is still less than three percent of India’s population, or less than five percent of adults. In contrast, “48.8 per cent of US families were direct or indirect owners of publicly traded stock in 2013” (SEBI source)

That means the rise and fall of the stock markets means nothing to over ninety-five percent of Indian adults. News items like ‘Bloodbath on Dalal Street‘ are utterly irrelevant to the vast, vast majority of people [3]. But correspondingly, when the market reaches an ‘all time high‘, like it did earlier this year, only a tiny, tiny fraction of people benefited from it – the purportedly immoral investors.

This needs to change. Both perception and reality.

So where are we at? I hope by this point we agree that it’s futile to treat ‘the market’ as an entity that has motives and morals.

That forcing share prices up or down in solidarity with the suffering or redemption of a country’s citizens doesn’t benefit those citizens, investors or companies. If anything, it harms them.

Finally, that in fact a powerful way to create wealth for citizens is, as far as possible, to have them participate directly in the growth of their country’s best companies, companies that contribute the most to the growth of the country’s economy. Today less than one in twenty Indians does.

[1] Why does it rise? To simplify greatly, say Infosys’ share price today is INR 100. If Infosys reports good numbers during the last few months, more people will want to hold Infosys shares. These people will be willing to buy shares at INR 101, because the expectation now is that the Infosys of tomorrow is even better than the Infosys of today. If enough people who already hold stock are OK selling their shares at INR 101, that now becomes the new price of Infosys. If not enough people are willing to sell, maybe others will offer INR 102. Or more. At some point, these two groups will reach an agreement.

[2] And of those fifty million accounts, over ten million were added in just the last year – young investors looking to participate in the market’s rise after the fall of February and March 2020. Until then, just about two and a half percent of India’s population had demat accounts. See below:

[3] When the same article says that the fall made ‘investors poorer by Rs 3.7 lakh crore in a single day’ it simply means that whoever bought the shares sold on that day will become richer by that same amount when the market recovers.