A lot of what I write is about data custody. It’s a topic that we’re inevitably going to have to debate in the mainstream sometime this decade – I mean prime time conversations on TV. That’ll happen when enough people experience the downsides of having their data reside with just a few large tech companies.

There are many ways things could go wrong with your data in the Cloud.

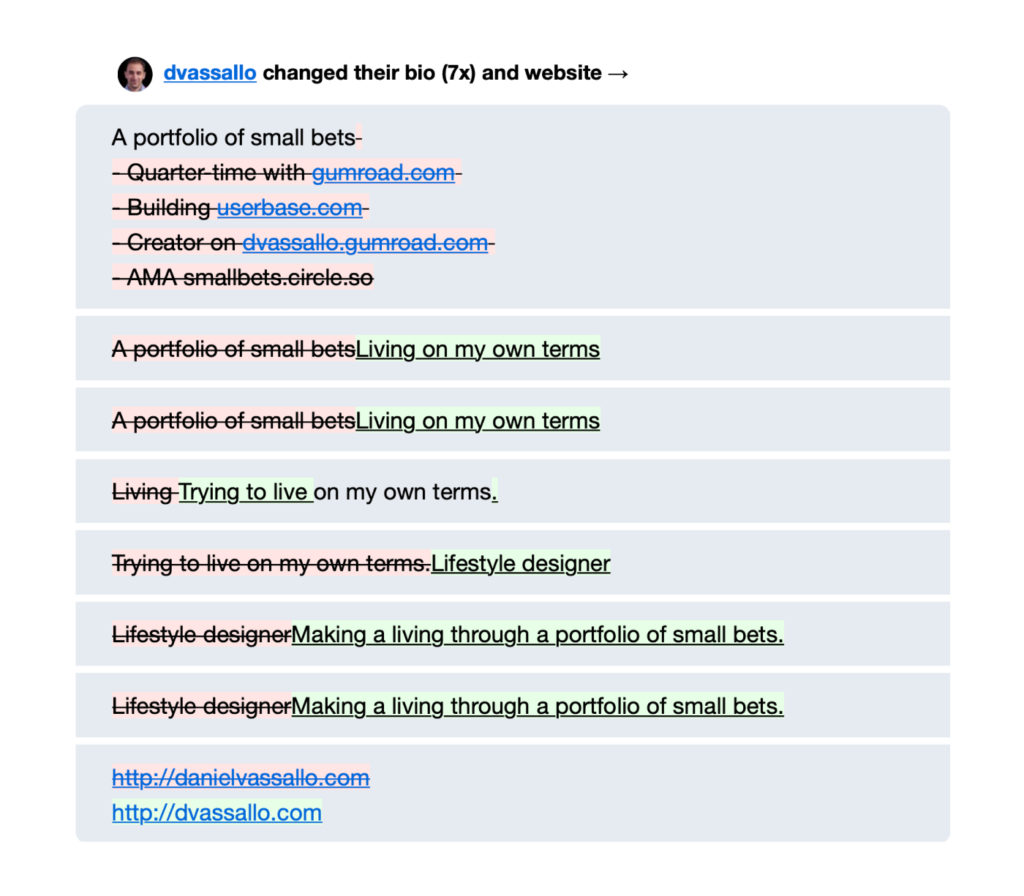

People could be locked out of their account for some violation of terms of service they weren’t even aware of, or being hacked via social engineering. If it’s their Google account, they lose access to their email, their photos, contacts. This has happened several times. We only rarely hear of it when it happens to someone with a large online following.

One of these companies may have a problem with their data centers. Even though people have access to their accounts, they could find their emails, documents, chats lost.

Companies could suffer an outage. This happens fairly regularly, most recently just a few days ago with the data organisation company Notion. If you can’t access your information at a critical moment – if you need to pull up a receipt number or a scan of a medical prescription – you lose trust in the company you stored your data with.

There are others still:

Governments could ban companies overnight, leaving you unable to access your data – India’s upcoming cryptocurrency law could do just that.

Companies could readjust free limits, leaving you with no choice but to begin paying them to hold your data – the upcoming changes to Google Photos’ free tier is an example.

You could find that there’s no easy way to export your data – if you move from an iPhone to an Android, it’s really hard to transfer the notes from your Notes app to an equivalent Android app.

The ‘cloud’ as the default for our life’s information and documents and photos – this is all very new. Email was probably the first to move to the cloud with Gmail, but even that was just fifteen years ago. That’s barely half a generation.

Each of us needs to spend at least some time thinking about how we’re going to deal with our data when we’re ten, twenty, thirty years older than today. How likely is it we’ll continue use iPhones or whatever they evolve to, to have several terabytes of info in our iCloud Drive or its successor(s), that we’ll keep buying Apple TVs to project our photos on? Ditto with Google. Or {giant trillion dollar corporation}.

We have collectively been exposed to billions of dollars of marketing to keep us from thinking about this, to believe that our data’s safe in the Cloud for now and forever.

To add to that, most of us aren’t ‘tech-savvy’ enough to even know what alternatives exist, much less be able to move to them and use them on an every day basis – why, even if you change your default browser, you’ll be asked if you want to switch back by the browser your computer shipped with (try it – change your default browser to Firefox on Mac OS; Safari will ask you right away if you want to switch back. Microsoft is even worse with Edge)

Finally, neither independent software makers nor open source projects been able to create software that, for the most part, can replace the entire gamut of Cloud-like software that the dominant tech companies provide. For instance, it’s not straightforward to organise your photos using something that’s not Apple Photos or Google Photos or Adobe Lightroom Classic – alternatives exist but they’re not great.

So. It’s not easy and it’s not a solved problem by any means.

Until the Cloud becomes a safe, reliable commodity like the electricity grid or the Internet itself, we’re going to have multiple independent Cloud islands. Apple’s. Google’s. Amazon’s. Microsoft’s. Yandex’s. Dropbox’s. Adobe’s. And a dozen more.

Each are closed worlds, but worlds that hold your life’s work and loves. And your only key, your username and password, isn’t guaranteed to always work.

It’s not sustainable.