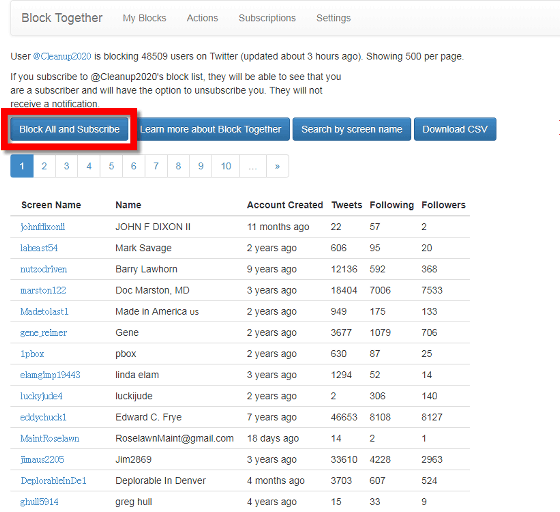

I woke on the 24th to news that Github, the source code hosting service had taken down the youtube-dl project repository along with many forks of the code maintained by other people. This was in response to a DMCA infringement notice filed by the music industry group RIAA.

In response to this distressing news, I wrote a Twitter thread, which I’ll reproduce here:

The youtube-dl project is no longer available on Github. A crying shame. youtube-dl is used not just to pirate – it’s also to archive videos of protests & rights violations before they’re taken down – depiction of violence is a violation of YT’s TOS! 1/

It’s to archive videos of public events, which may have nothing to do with music. Even when they do have to do with music, as this artist says, youtube-dl was why he had a copy of his *own* performance: 2/

I use the tool occasionally to create a copy of rare versions of 50-year-old+ Hindi film songs that perhaps a few dozen people are interested in anymore, and which you won’t find on iTunes or any store. But they’ll be lost to the world if that YT account ever goes offline. 3/

youtube-dl will likely be down until the creators find an alternative repository, which will likely also be an RIAA target, very likely pushing it onto the Tor network, which’ll definitely get it labelled in the mainstream press as a piracy enabler – that‘ll be the narrative. 4/

More than anything, Github’ acquiescence sets a very worrying precedent. As this tweet says, cURL (& wget) are widely used open-source projects to download a wide variety of content. You could make the same case to shut these projects’ hosting down. 5/

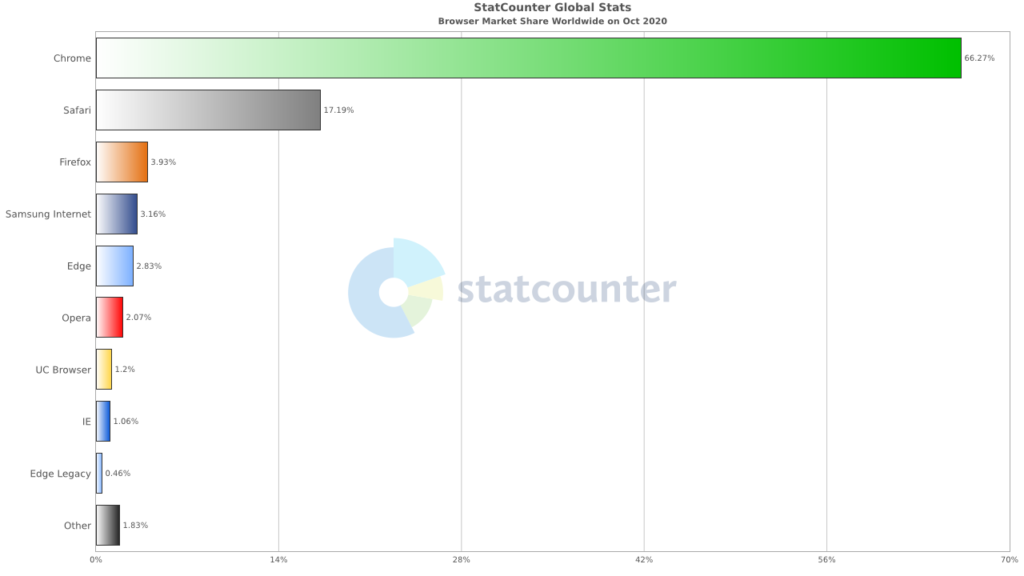

This should be a loud wake-up call for the @mozilla Foundation, the Electronic Frontier Foundation , the Free Software Foundation – on their watch, a Microsoft business unit became the world’s most popular code hosting service, including for critical Internet projects 6/

The FSF had plans for its own code hosting service in Feb but it doesn’t look like they’ve reached a decision, much less begun execution. Sadly, paid, full-time teams will almost always execute *faster* than volunteer teams like in the FOSS world. 7/ https://libreplanet.org/wiki/FSF_2020

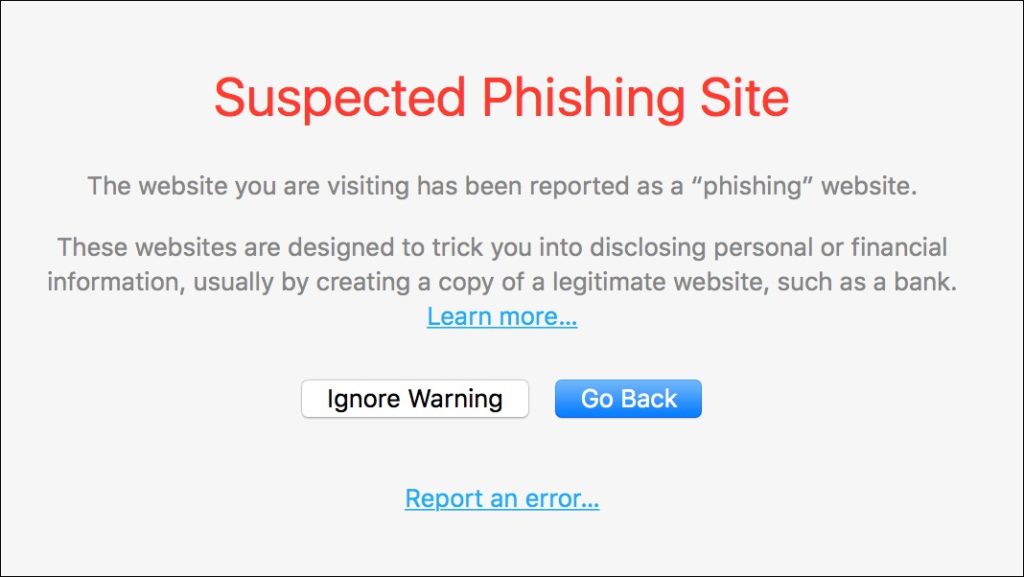

Censorship-resistance needs to be a top-level criterion for evaluation, for anyone who is building anything of value for the Internet. A strictly free (or open source) code hosting platform is of no use if it or its projects can be taken down just like with youtube-dl. 8/

This should be an equally strident wake-up call for other projects – such as @The_Pi_Hole, which I have written about so often, and which are hosted on github. If the RIAA has gotten its way, the much larger online advertising industry could very easily act next. 9/

There are so many other projects that survive publicly ONLY because they either fly under the radar or have not yet been targeted. Two that immediately come to mind are the Calibre project and its (independent) Kindle De-DRM plugin. 10/

End note: I had written about how you could create a censorship-resistant site on the Internet. I’d written this as a lightweight thought experiment. Today I see it in a more serious, a more urgent light. 11/11 (ends).

Another thought that struck me after the thread is that a USA-centric industry association filed a notice under USA law to a USA-based company, Github/Microsoft, and knocked offline a project that

- had contributors from all over the world

- was forked by people all over the world

- made a tool that was used by people from across the world

- to download videos and knowledge created and posted by people from around the world

We think of the Internet as a shared resource. Practically, it is subject to the laws of just a few countries, especially the USA, and a few massive companies, also mostly registered in, and subject to the laws of, the USA. This is not a criticism of the country – such centralisation of authority and control in the hands of any one or few countries is detrimental to the future of the Internet as we know it.

I will probably have more to say about this, but this is it for this post.