We’ve often spoken on this site about ad and tracker spam on the web. But this year there’s also been an increase in spam across other mediums – phone, SMS, Whatsapp, Linkedin, Twitter and email. It’s likely this is partly because there are vastly fewer people outdoors, making any form of real-world advertising and messaging ineffective.

In any case, our messaging apps are our highest-priority inboxes. We leave notifications on because chat is both asynchronous and real-time, both personal and work related. That’s why spam on these messaging apps make a higher claim on our attention than, say, email.

Given how fragile and limited our attention is , we must take such casual abuse of attention very seriously. Each of these apps has methods to report and/or block spam. We should all use them mercilessly. It just makes your life better.

But not only is the payoff high for you, your effort makes other people’s online lives better too, by taking spammer accounts offline. None of the services we’ve listed above – and others ones you use – are decentralised. Certainly not Whatsapp, Linkedin, Twitter. Email’s become synonymous with Gmail. Your reporting and marking as spam blacklists that account for everyone else on the service. We have often discussed the dangers of ceding control of your data to large tech companies, but in this case we can use it to our advantage.

Spam is a community problem – and the only way we’ll tackle it is as a community.

Phone and SMS

India has had a do-not-distrub regulatory framework for dealing with spam for over ten years now. First, find out from your mobile operator how to get on the do-not-call registry. As of this writing, you can also send ‘START 0’ as an SMS to 1909 to opt-out of all promotional messages – but as with most government services, this doesn’t always work.

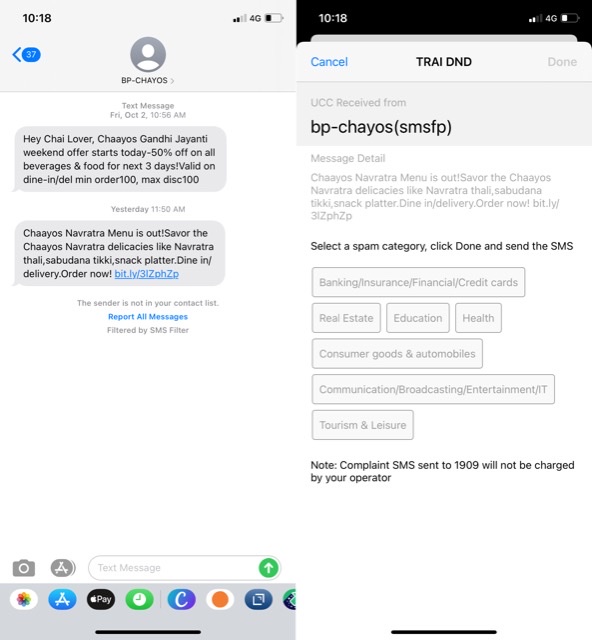

Then install the TRAI DND reporting app (iOS App Store, Google Play Store). Report every single spam SMS and phone call you get. Here’s me reporting spam:

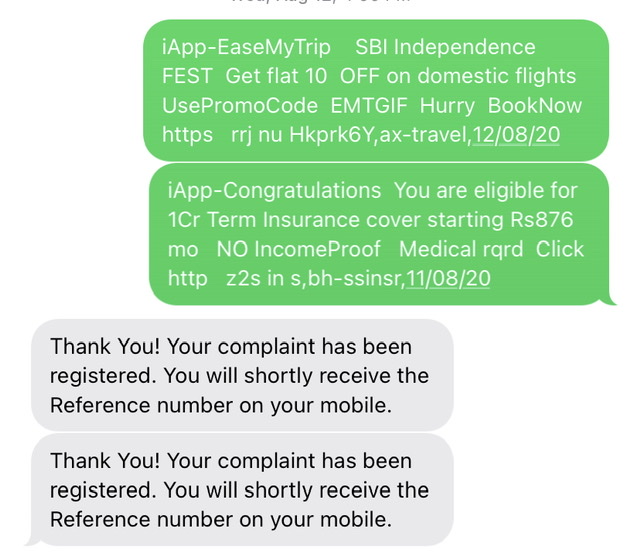

Here’s a screenshot of my operator confirming complaints from other spammers:

I’m sure this doesn’t work 100%. See this article from the publication Moneylife on TRAI’s ineffectiveness. But I have seen a sharp decline in the SMS and phone spam I receive now versus a couple of years ago.

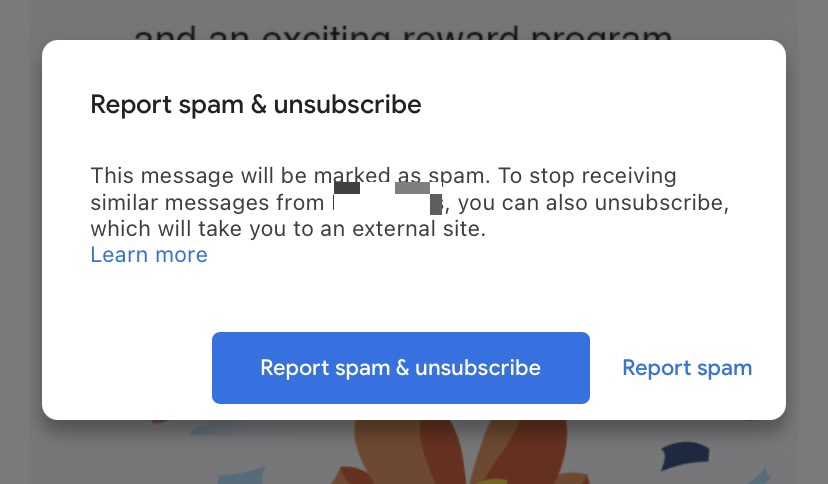

On Gmail, when you report as spam, don’t bother with the ‘report spam and unsubscribe’ option that Gmail presents you. Bad actors take your unsubscribe response itself as proof that your account is active, resulting in further spam. Just stick to ‘report spam’:

If you’re using Gmail in another email app like Apple’s Mail.app, don’t mark as spam in that app – that feeds Apple’s filters. Take the trouble of addressing the problem at its source – go to the Gmail site or the Gmail app and mark as spam there.

Messaging apps

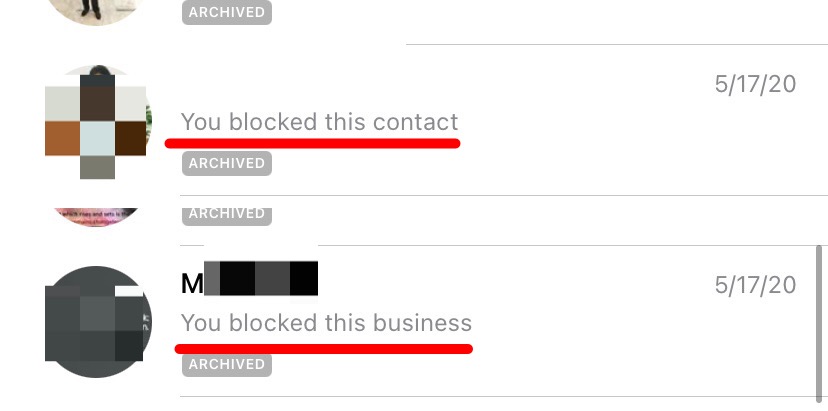

As for Whatsapp and Linkedin and other messaging services – reporting and blocking is 100% effective for you, and goes a long way to making sure that account doesn’t bother anyone else:

We are even more powerful on these new mediums: Whatsapp is tied to your phone number. If enough people report a spammer on Whatsapp, we’ll end up knocking that number off the service. The spammer now needs to get a new phone number, which requires going to a store and performing KYC. And yes, KYC in India can be spoofed, but the costs of getting a new number and a new SIM card are much higher than creating hundreds of new email addresses to spam from.

We can win

Just as spamming is asymmetric – a small number of spammers can impact many orders of magnitude more people – marking as spam is also asymmetrical. It only takes a small number of us to take a lot of spammers offline.

Let’s do this.