An old observation of mine has been that the more powerful and plentiful our devices get, the longer they spend idle. I call it the Tragedy of the No-Op.

(A No-Op or NOP is a machine language instruction that tells the processor to do nothing, an empty cycle).

The processor on a Nokia ‘dumbphone’ spent a greater percentage of its lifetime cycles working for its owner than today’s iPhone. Or iPads, Macs, Echos, routers, smart home switches, TVs, or connected cars.

We own more computers today than ever. And each of those gets more powerful each year – and they stay idle more and more. An Echo mostly just stands there checking “did someone say Alexa?” over and over for well over 99% of its life.

I’m pro-abundance – to coin a term – so I’, reluctant to call this idle computing power a waste. But I do wonder if we can put all this silicon to better use.

For example: Bitcoin mining is now increasingly concentrated among a small set of mining pools because bitcoin now requires miners to run specialised hardware, ASICs, to be competitive earning mining rewards. Ethereum also requires high end graphics-processing-units or GPUs. The demand for GPUs got to the point where in May last year Nvidia designed a graphics card that would cripple its own performance if it detected its use for crypto mining.

It’s the same for storage: most of us have inexpensive hard drives and pen derives, and hundreds of GBs of free space on our laptops and iPads and phones, and yet decentralised storage projects require massive amounts of high-end solid state drives connected to powerful computers to be viable.

So here we all are, with more combined computing resources than ever across all our devices but today’s proof of work/space blockchains are such that they require even *more* hardware, affordable by a very few – far from their ideal of decentralising trust and opportunity and value creation.

What will new blockchains that can run on billions of devices look like? What new use cases will they make possible? What effect will they have on wealth creation? What incentives will they create for low-cost devices and even cheaper, ubiquitous connectivity?

Like with every seemingly intractable problem, this is a massive opportunity. I wonder what tomorrow’s solutions to these will look like.

Category: Uncategorized

Intimacy doesn’t scale

I think a significant part of the problems with today’s social media design is the lack of context, whether it is photos on Instagram or posts on Facebook.

You scroll through a feed. You tap on a post. You read the caption. That’s all you have to divine the poster’s background, intent, state of mind, everything.

So the engagement between the poster and their readers/viewers is shallow. It’s expressed in one-tap likes or thumbs-ups. It’s expressed in one-tap re-tweets. It’s expressed in single-line comments that might as well have been emojis. LinkedIn even suggests emotive canned reactions, complete with exclamation marks (“That’s great!” and “Has it been a year already!”).

Very quickly the poster begins sharing with the expectation of mass visibility but low-engagement. Readers scroll past even faster, ignoring dozens of posts wholesale, and tap-tap-ing their reactions on a few. Tapping and expanding to read a message and is attached photos is breaking rhythm (leave alone reading a message’s other comments or tapping an attached link).

Once this becomes the norm, the whole act of expressing oneself on social media takes on a hollow, performative look. Our real selves move to other places like our messaging inboxes & small family groups – the dark forests of the Internet.

This extract from a blog post I stumbled upon says it well:

… thinking about photo sharing in general. And more specifically about how we’ve created this efficient system for sharing to a mass audience. The personal aspect of photos is lost in the sharing process.

When I would post a photo, I wouldn’t receive any comments, it never sparked any conversations. I would just get a handful of likes and that was that. What’s the point? It’s become a game of vanity where the number of likes you receive is the only feedback mechanism. It stinks.

As an experiment, I started sharing photos with individual people, privately, over iMessage. I wouldn’t send them a whole collection of photos, just one at a time here and there. And what I found is that when you send an individual person a photo privately, you actually spark a conversation.

– https://initialcharge.net/2022/01/thoughts-on-photo-sharing/

The design of social media simply doesn’t lend itself well to the sort of engagement that the writer sought. From its earliest days, social media has sought to optimise for scale. At the beginning it made sense because the more people there were on a service the more, well, social it’d be.

But these services also began optimising for increased engagement between users. Increasing followers and followed. Encouraging frequent posting. Encouraging limitless scrolling. If you expend much of your cognitive bandwidth on breadth of coverage, precious little is left for depth of interaction.

Group chats have proved to be a reasonable alternative to social media. I wonder what that will evolve to.

Contemplate experience

This piece is from 2020, but – as often with paper journals – evergreen:

One student, a slight girl with dark eyes, dark hair, and a sweet determined demeanor, had the most beautiful journal I had ever seen. It was a small red book inside of which she both wrote and made collages from the scraps of papers she shed just walking through her life—ticket stubs and business cards, a photograph, seashells collected on vacation, sand—it was all glued into her book. Words wove their way around the images.

Hers was a combination of scrapbook, journal, and artwork, mesmerizing to look at and, she told me, calming to create. She gave herself time each day to spend with the journal. It freed her, allowed her to contemplate experience, process it.

Detail

You can see this everywhere if you look. For example, you’ve probably had the experience of doing something for the first time, maybe growing vegetables or using a Haskell package for the first time, and being frustrated by how many annoying snags there were. Then you got more practice and then you told yourself ‘man, it was so simple all along, I don’t know why I had so much trouble’. We run into a fundamental property of the universe and mistake it for a personal failing.

– “Reality has a surprising amount of detail”, John Salvatier.

The writer makes the case that when you examine tasks and phenomena because you are stuck, you uncover detail you’ve missed. And details you thought were important get put into perspective.

In the years I followed a regular meditation practice, I’d have days when interactions seemed to occur in higher resolution than usual. Visually I’d notice people’s cues and expressions. Aurally I’d be aware of the timbre of that person’s voice. As someone new to this it became too much to process. But that detail, and the sense of slowing down of time, meant that interactions also became more intuitive.

Of course the writer isn’t taking about mediation or HD interactions. He simply makes the case, quite well, that when you pay attention, “the important details you haven’t noticed are invisible to you, and the details you have noticed seem completely obvious and you see right through them.”

And yet it seems smaller

In the nineties, the internet seemed to be a vast endless expanse of wonder and weirdness. Because it was. Especially before any localisation or personalisation.

In the nearly thirty years since, the internet, particularly the web, has exploded, and now it’s orders of magnitude bigger: more people from more countries, more domains, more types of stuff online, more types of devices – and way faster pipes.

And yet it seems smaller. The relentless optimisation by search engines and social media (well, Google and Facebook) has de-weirded the Internet, stripped it of its long tail. Everyone’s talking, but it’s about the same set of things.

I think we need more entry points to the Internet to get some of that magic back. Social media doesn’t cut it, not even Reddit, at one time the Front Page of the Internet. And metafilter survives valiantly, but as a shadowy of its former self (or perhaps in the shadow of what is now the giant corporate internet).

What are some worthy successors to StumbleUpon, Digg and del.icio.us?

What value does the token capture?

A friend brought to my notice this important comment, ostensibly about crypto tokens:

same thread:

With Bitcoin and other digital-money-type cryptocurrencies, this point of view is understandable. The total mined Bitcoins are now worth nearly two trillion dollars (no one yet denominates items in Bitcoin; the US dollar has that locked down). Millions of people trade bitcoin 24×7, institutions hold it, firms create derivative instruments for it, publications cover it, social media chats constantly about it.

And yet, there are very few applications of Bitcoin outside of it being a speculative asset. It has not displaced the dollar or even threatened to do so.

Events in Syria, Afghanistan, Venezuela, Lebanon and other countries have severely devalued people’s savings in their local currency, but we have yet to see a wholesale shift to bitcoin. This is for several reasons, not necessarily a lack of trust in an all-digital currency, But the fact remains.

The decentralised finance world is similar but slightly less straightforward. Hundreds of projects doing very interesting things have their own native token. Several people do their research, identify which projects actually have teams, are building products, have pedigreed backers, and then buy and hold the native tokens of such projects. The expectation – and basis for speculation – is should the project do well, the token will rise in value too.

That isn’t necessarily true. The research should also look at what the native token represents. How much of the value that the project creates does the token capture?

It is a lubricant in transactions in the project ecosystem? In that case, how does holding the token cause its value to appreciate (other than you holding so much that you cause scarcity).

Does the token aid proof of stake? In that case, how distributed is the network? Does your holding the token aid one of just a few concentrated pools?

Does the token confer voting power on decisions? In that case, who (or what) decides what is brought to a vote or not? Are decisions binding? How diverse is the voting pool?

Did the project’s backers get some exposure to their project’s native tokens themselves? If not, why are they not aligning themselves with the project’s value capture?

This research is not radically different from that in the world of traditional finance. If you aren’t doing this, it’s fine – then do make peace with the fact that your crypto holdings and trades are just that – speculation.

Every month I get a receipt from Apple about my monthly iCloud Drive charge.

It’s a reminder of the fact that in addition to all the hard drives I’ve bought from Apple – in my computers, phone and tablet – I also rent one from them, in perpetuity.

All in order to keep data on the other hard drives in sync.

It made sense at one time. When Apple’s free iCloud tier offered 5GB of space, and they sold iPhones with 8GB of storage. Then, it was a secure, private way to store data that wouldn’t fit on your phone.

Today, ten years later, all of Apple’s iPhones and iPads start at eight times that, 64GB storage. And the latest iPhones 13, and all iPads Pro have a minimum of 128GB.

Meanwhile, the base iCloud tier is still 5GB.

Because Apple’s model is a client-server one – iCloud in the center, all of a person’s Apple devices (iPhones, iPads, Macs, Apple Watches, Apple TVs) around it – there’s no way that the base storage tier is enough for anyone’s data. And everyone ends up paying for what is effectively a rented hard drive from Apple. An intelligent one, but a hard drive nevertheless.

But most people have their devices in close proximity to each other. They’re usually connected to high speed wireless networks throughout nearly every day. An alternative model could easily have been one where each of these devices stay in sync in a mutual, peer to peer structure. If you have a don’t own a Mac, Apple could extend the Windows iCloud client to sync your data.

With this, you don’t pay for as much storage online. And Apple’s data centre scale reduces a bit. You also don’t connect to the public internet. That saves data, frees up bandwidth and is a lot more private.

A peer to peer model would fit in a lot better with Apple’s very public commitment to the environment and to privacy.

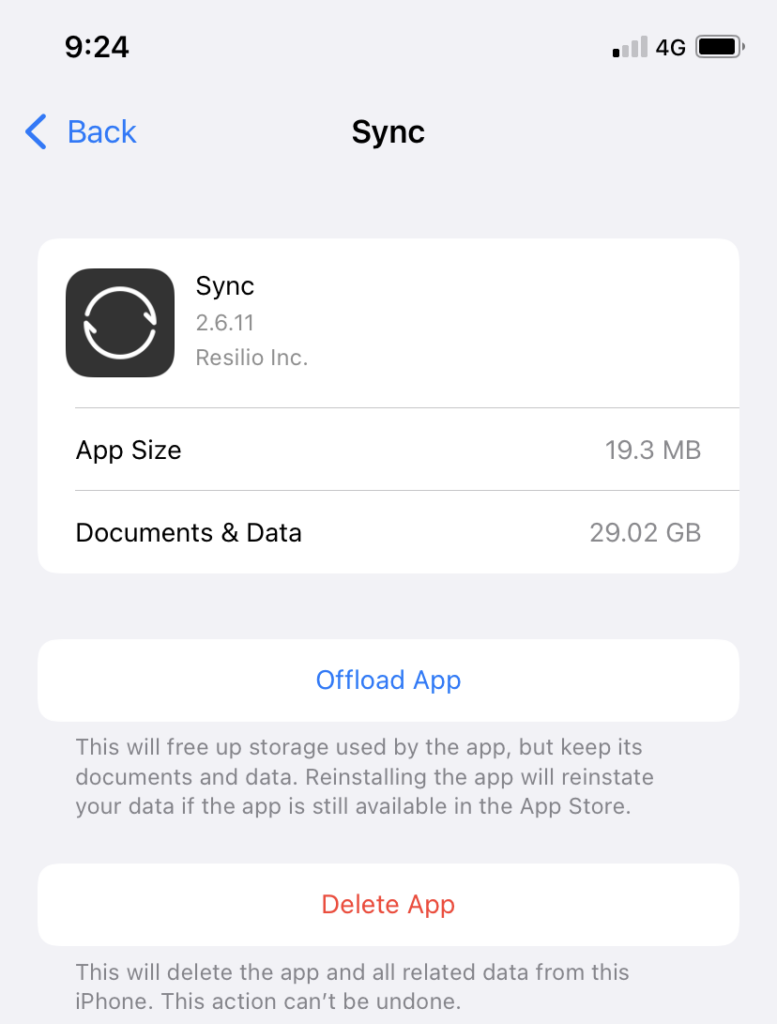

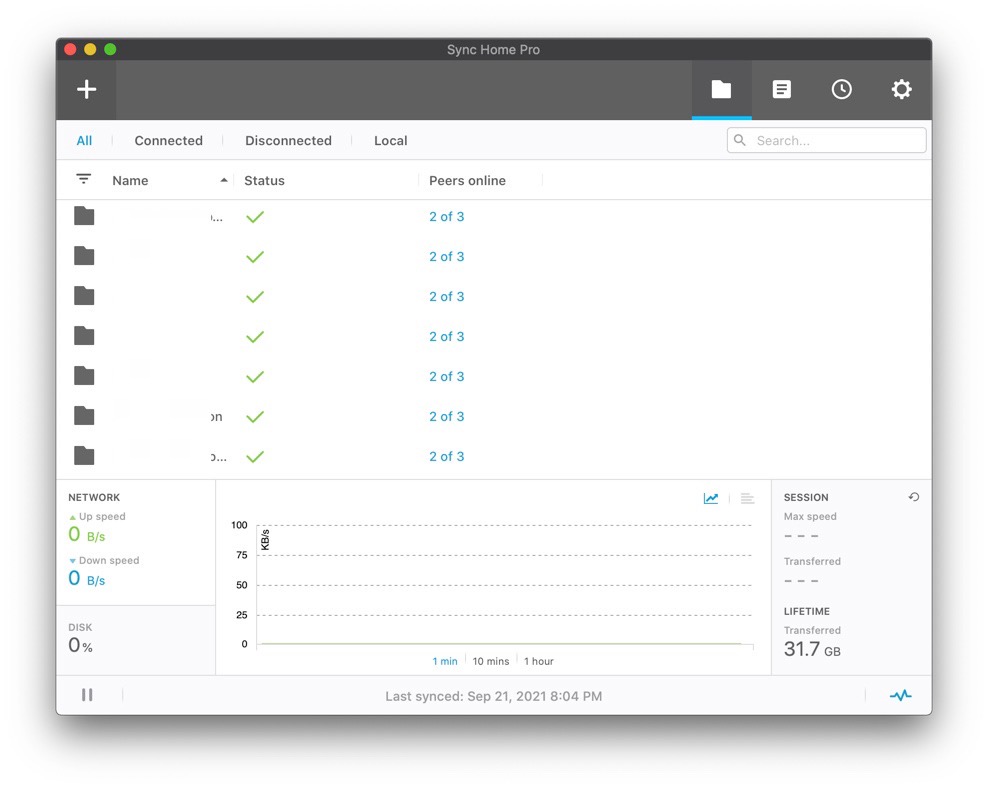

I’ve moved most of the documents I don’t use very often to a peer to peer system via Resilio Sync (for which I have a family license). I have a dozen GB synced between three Macs, one iPhone and one iPad without needing an Internet connection:

Neither my iPhone nor iPad use iCloud Backup – they are both backed up to my Mac weekly. That saves me over fifty GB of space I would have otherwise paid for. It’ll also mean I can set up a new iPhone a lot faster than from iCloud.

Ours are the first generations to accumulate digital data through our entire lifetimes: documents, files, photos, videos, music. Each of us will easily have several terabytes of data. At some point, paying today’s rates to store all that information online is going to cost too much money.

Maybe we’ll have near-ubiquitous connectivity, essentially free bandwidth and rock-bottom rates for cloud storage, all with the guarantee of security, resilience and privacy. I’d love to see that come to pass.

Until then, I think we need to consider how we’re going to manage our data the way we did just ten years ago – ourselves, on our own machines.

Systems over goals

The writer James Clear, in an interview with the excellent Morning Brew newsletter :

What is one of your ideas that most resonates with your audience?

There are probably two. The first is the idea of systems over goals, or rather than worrying about the outcome, focusing on the process and building better habits each day. The line that people bring up a lot from the book is, “You don’t rise to the level of your goals, you fall to the level of your systems.”

The other one that has gone over well is what I call “identity-based habits.” Rather than worrying about the results you want, focus on becoming the type of person who could achieve those results. So instead of worrying about losing 40 pounds, focus on being the kind of person who doesn’t miss workouts. Or rather than worrying about finishing the novel, focus on being the kind of person who writes every day.

I haven’t yet read Clear’s book Atomic Habits, but I found both of these useful ways to frame one’s goals, especially as someone who values systems and sustainability, as we’ve explored several times on this site.

They also potentially nudge you away from unhealthy behaviours: a brute force approach, or self guilt/self recrimination, overcoming both of which has been a long – and ultimately successful – struggle for me.

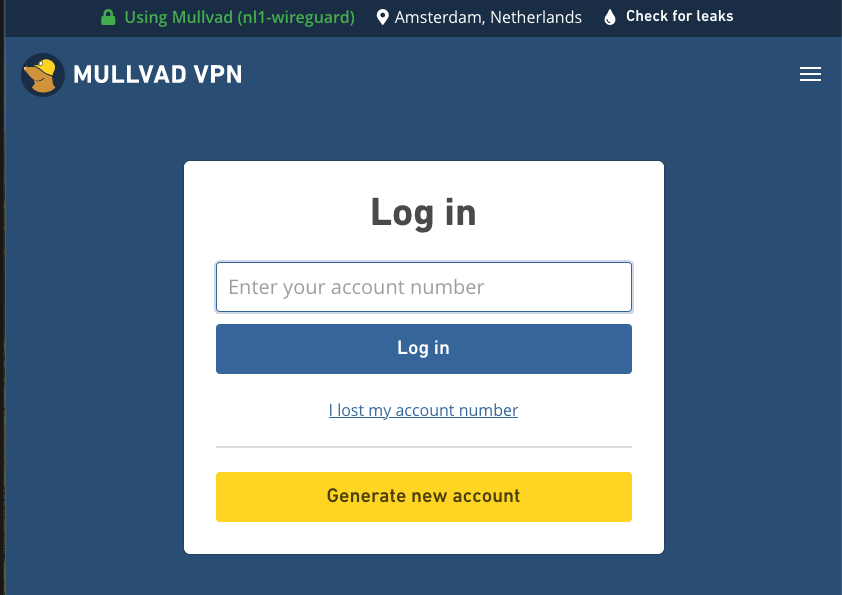

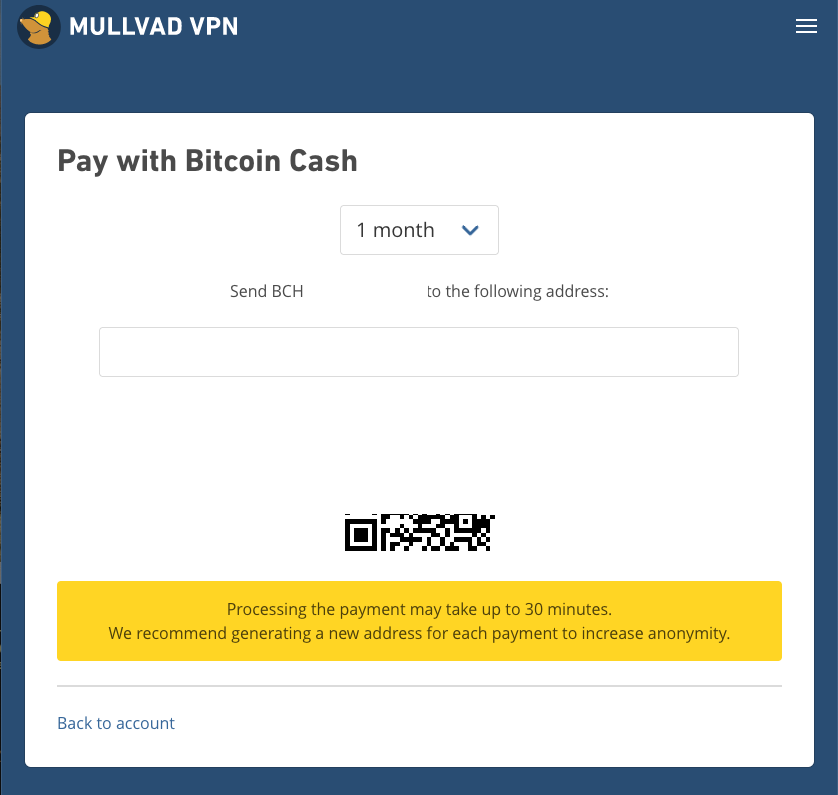

I recently paid for my VPN service with cryptocurrency.

The service is designed so it knows nothing about my identity.

No signup – just a string as user ID.

It accepts cryptocurrency (Bitcoin and Bitcoin Cash), and even adds a 10% discount.

There is no real account management with profile or settings. Just VPN keys to be generated.

The service itself claims to not log anything, and audits itself regularly.

We want you to remain anonymous. When you sign up for Mullvad, we do not ask for any personal information – no username, no password, no email address. Instead, a random account number is generated, a so-called numbered account. This number is the only identifier a person needs in order to use a Mullvad account. This is a fundamental difference that sets us apart from most other services.

and

We log nothing whatsoever that can be connected to a numbered account’s activity

– No-logging of user activity policy.

Not having to deal with all of this overhead makes using the service magical. It also means that for the team, the definition of the product is very narrow – just the VPN service, nothing else. No log management, customer profile management, ad partner management and on and on – nothing that’s not core to the service. They get paid for what they deliver.

It has to be just a matter of time before this frictionlessness becomes the norm.

The balance of power has shifted

Generally speaking, at this point, I am getting a little tired of technology books. They all seem to stick to variations on the same theme: tech is evil. I happen to disagree with this premise, but perhaps it is what sells… they all seem to be grasping at opportunities to spotlight the bad apples.

Technology has ceased to be a wonder.

Today tech both suffuses our lives and regiments them.

Boxed software used to be just tools to work and toys to play with. The contract was clear.

But nearly all software today are designed to get you to use them a certain way. Software, or software services, are as much about you gaining value from them as the other way round.

The balance of power has shifted towards those who make our technology, and we’re not happy.

It is that dissatisfaction that we’re seeing expressed through pop culture, through our TV shows, movies and books.